BubbleSort Zines founder, Amy Wibowo. Image description: A portrait featuring Amy. She/they are pictured in the center and looking off to the right on a navy blue background. Image courtesy Techies Project.

For the New York Tech Zine Fair, I interviewed founder, editor and CEO of BubbleSort Zines, Amy Wibowo.

Amy is a programmer who left the tech industry to pursue her life’s work of making zines for women, femmes and non-binary folks who feel alienated by gender discrimination within and out of the computer science field. Amy will be a featured vendor at the first ever New York Tech Zine Fair on Dec. 1 from 12 to 7 p.m. at the School for Poetic Computation.

Your zines involve a lot of research, care and content and often extend to upwards of 100 pages. What is your zine-making process?

Amy: There’s a lot of research. I did study computer science formally, so sometimes I go back and look at my notes and my textbooks. I try to think about what concepts were most exciting to me, what concepts were the most difficult to me, and get myself back into the mindset of when I first learned about these things. A lot of writing, a lot of drawing. I tend to alternate between the two — like, when I’m tired of writing, I work on the illustrations and when I’m tired of illustrating, I go back to writing.

It’s really important to me that people can understand the zines even if they don’t have a computer science background or heavy math background. I have a test reader who’s a high school student go through all the zines and tell me if certain parts are boring, if certain parts are hard to understand. They will let me know I need to rewrite those sections. The drawings make a big difference. Her feedback is often, “more drawings, please!”

It’s also important for me to make sure the content I’m writing is not only easy to understand, but technically accurate. I’m not an expert in every subject in computer science by any means, so I make sure to get someone who is an expert in a subject that I’m writing to read through the zine and make sure the analogies I use make sense or the way I introduce the subject won’t cause misunderstandings or be a problem if the reader wants to go into the subject more deeply later. Then, a lot of revising and editing. Maybe 90 percent of my time is actually re-writing the zine.

How long is the process from start to finish?

A: About 6 months.

An assortment of BubbleSort Zines. Image description: A top down view of zines spread out like a fan surrounded by femme lego toys, plushies, hearts and pink, pastel pink and fuchsia art markers. One of the zine’s titles can be read as “How do calculators even.” Are there any specific printing, zine-making techniques you consider integral to the BubbleSort look?

A: I don’t print them myself. I get them printed locally. As a small, woman run, independent business, I try to find — in any part of my process — other small, independent woman run businesses as well. I have a connection with a woman run, local printer in Oakland. It’s important to me in my process to support other small, marginalized independent business. When I hire test readers, I prioritize finding ones that are femme or queer or people of color and/or intersections of all those.

Do you find it challenging to find people within those intersections?

A: So far it hasn’t been a problem. I usually tweet asking if there’s any interest for whatever particular thing I need — models, photographers, readers and the internet is usually quick to provide. For me, it has the bonus of my business getting to pay other marginalized people which makes me happy too.

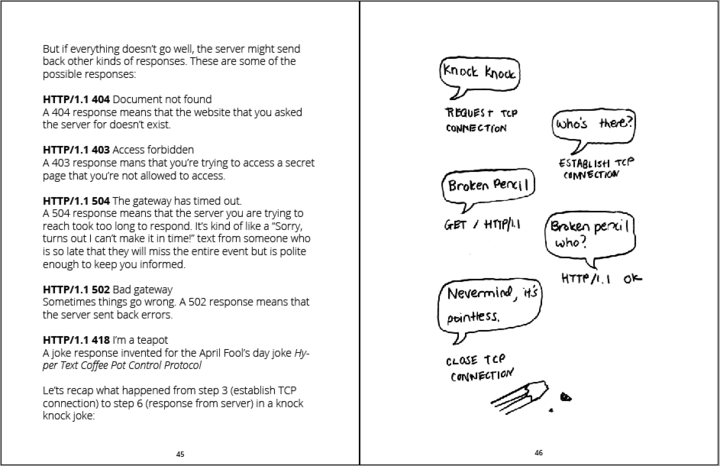

Screenshot of a spread from Amy Wibowo’s “How does the internet” zine.

I understand crowdsourcing is an important factor in your process. How would you describe your relationship with people on social media or, more generally, the audience who interacts with your zines?

A: I feel really lucky to have the audience that I do. My audience is anyone who cares about computer science. I think my youngest readers are 8 years old. I have 70 year old women stop by my booth at a zine fest and tell me they’re really curious about how the internet works and then buy a zine about how the internet works. I feel like my audience is really supportive of my work. It makes me feel really happy and touched when I get emails from people saying that my zines helped them get through a computer science class or helped their daughter discover an interest in computer science. I hope through my zines I can be kind of like a personal cheerleader for anyone when they’re feeling discouraged about tech and computer science.

When you were first getting into computer science, were there times where you felt like giving up?

A: I felt pretty lucky when I was doing computer science in college in that, I went to an engineering school, but lived in an all women’s dorm. In all of my classes, I always had groups of women that I would work with. It was more of a shock when I graduated and started working to see that wouldn’t always be the case. I do remember in some of my college classes, I was criticized for being femme and having a feminine approach to computer science. I remember peer reviews telling me that —

From your fellow femme/women peers?

A: No, male peers telling me that my final project presentation was too pink. That definitely informs my process now.

Every time I’m criticized for my work being too feminine, I just want to make it more feminine.

With your zines being more feminine, does your audience reflect that? Are people who you didn’t expect to your zines to resonate with interacting and engaging with your work?

A: One thing that makes me happy is that I definitely receive emails from men thanking me for not calling them “zines for women” because there are a lot of men and non-binary people who also like cute and feminine things and are often excluded from a traditional focus in computer science.

What do you think sets apart your zines from other tech zines?

A: The things I try to focus on in particular are history and art that aren’t often connected to computer science.

I try to decolonize computer science education.

A lot of CS classes will focus on contributions from white, western men. There are lot of interesting contributions from other cultures and women and people of color and intersections of all of those. I try to make sure to emphasize those. I also try to focus on the bigger picture and things that might be helpful to learn even if someone doesn’t end up going into computer science. I feel like technology is increasingly more and more a part of everyday life, so it’s useful for people to learn about security or how the internet works even if they don’t end up studying computer science.

In your research of a non western computer science history, who are some of the figures you were surprised or inspired by?

A: This is not a specific person, but I thought it was really cool that a lot of cryptographic advancements were made by Muslim scholars of the Quran. It happened many centuries before western cryptographers made the same discoveries. A lot of times it’s cultural discoveries and not just individual discoveries.

You talk a lot about reframing computer science as magical in efforts to make it accessible and inclusive to people who might not think there is a place for them in computer science. Why is it important to reframe and/or decolonize computer science as non western and/or more magical to challenge the prescriptive way we understand computer science?

A: One thing that happens as a result of the typical framing of computer science as very logical and scientific is people can often feel like it’s infallible or impossible for it to be biased or that it’s completely neutral and non political, when it’s not any of those things because computer science is something done by humans and humans can be biased and racist and yeah, infuse everything they do with politics. It’s important to remember that computer science is something very human.

“I feel like zine culture is telling me ‘anyway that you are, anyway that your zines are, that’s valid.’”

I think the current preconception of computer science also includes who can be in tech and who can be a programmer and that’s something I want to see eliminated. Whereas the perception of computer science as magic I feel is something that’s more for everyone. I also think there are preconceptions of what sorts of things you can do with technology, like building apps and websites similar to the ones that already exist. I like the idea of framing computer science around fiction, fantasy or science fiction to help people not be locked into the ideas or apps and websites they’ve already seen.

The narratives around technology today can be very dystopian. How do you hold onto and share the magic you find in computer science and tech despite all the negativity surrounding it?

A: It can be really hard, but that’s actually my primary motivation for everything I do. In fact, I’ve been trying to rediscover the magic I used to feel about computer science right when I started learning it and then pass that onto other people. It’s almost always through a personal creative project connecting computer science to knitting or origami or cross stitching or embroidery or other crafts that makes me rekindle the magic.

Can you recall a moment you felt magic with a computer?

I remember learning about logic circuits for the first time and feeling like that was really magical because I always used calculators but never understood how they worked. I knew it was possible for machines to do physical labor for us, but it felt really magical to learn about how they could also do thinking and computational work for us.

“Hello world” illustration by Amy Wibowo.

How have you felt entering the zine community as feminine person compared to the tech industry?

A: Oh, it felt so much more welcoming. As a person who is typically in tech spaces, entering zine spaces feels like a great recharge for my soul. First of all, seeing the types of people in the zine community — there are so many more people of color and queer people. The kinds of things people write zines about — zines about sexuality or being an immigrant or being mixed raced and knowing that there’s an audience for each of these things. Things are so personal. Everyone who writes zines about each of these topics — they’re like pouring their heart and soul into it. When I read zines I feel really connected to the people who wrote them.

I’m curious about your transition and whether or not you experienced any growing pains in the shift from the tech industry into the zine community. Did you experience imposter syndrome or feel like you were making a mistake?

A: One thing I love about the zine community and zine culture is I feel like it’s really hard to feel imposter syndrome in it because there are such a wide ranges of zines — zines that are hand written, zines that are photo copied — it feels so validating. I feel like zine culture is telling me “anyway that you are, anyway that your zines are, that’s valid.” In the past, I’ve thought about writing a computer science textbook or book, but with writing books I often think to myself, “oh i don’t know that I know enough yet to write a book, I don’t consider myself an expert.”I feel like there isn’t that kind of gatekeeping in the zine community. However much I know about a subject, it’s okay for me to write a zine about it. I can not know about a subject and learn about it and write about it. So that’s been really nice and fulfilling compared to the tech industry.

One thing is that, most people making zines, don’t make zines as there primary source of income. So trying to figure out the business piece, the sustainability piece has been difficult and I’ve had to learn a lot to figure how to make a sustainable amount of money running a zine business compared to the tech industry where I felt very spoiled. Tech salaries are much easier to live on. It’s definitely a process. I feel more hopeful about it, there are still definitely some struggles, especially living in San Francisco which is not a cheap place to live.

I have also been branching out into apparel. There are ways that the apparel side of my business is helping keep the zines and educational side of my business more sustainable. A couple weeks of designing a shirt will bring in just as much money as six months of researching and writing a zine. I’m trying to figure out ways that still resonate with my core mission of making computer science more inclusive, but still make my business more sustainable.

BubbleSort bomber jackets. Image description: Four models pictured sitting at a counter while showing off the back of their jackets which read “git it gurl” in cursive hand lettering surrounded by illustrations of cherries.

How do you keep your zines in conversation with your merch?

A: I’ve thought a lot about how there’s kind of a tech bro uniform of hoodies and jeans and I feel like that’s one of the methods of gatekeeping feminine people out of computer science and programming. It’s very clear feminine people don’t have that uniform. A lot of my merch has pastel colors and also includes technical jokes or technical references. Instead of a programming hoodie, I’m making programming satin bomber jackets.

This might be a redundant question given our conversation, but I do want to verify whether or not you consider yourself to be critical toward the tech industry. If so, what are the challenges?

A: Yeah, I still consider myself to be very critical toward the tech industry which is kind of interesting, contradictory, ironic because I am writing resources to teach computer science.

While wanting to make computer science more inclusive for the people who are entering it, I continue to be more critical of the tech industry so it deserves all of the marginalized people that are entering it. So many things bother me the way the tech industry thinks of itself as above and beyond ethics or law, thinking of itself as more important than art or the humanities, the way it continues to gatekeep marginalized people, the way that so many algorithms are biased against dark skinned people — so much of that needs fixing.

Part of your criticality involves a lot of emotional and intellectual labor to help people, particularly cis men and their collaborators, understand femininity isn’t a sign of unintelligence and the tech industry should be more inclusive. How do you navigate knowing when to explain yourself vs conserve your energy to people who discriminate against you and the people you’re making space for in this industry?

A: It’s really hard. I’ve shifted more and more toward letting my work speak for itself. If I’m feeling like I have some extra energy, I’ll sometimes try to explain to people who question what I do — if they’re a friend, a colleague, or a friend of a friend — people who I’m more adjacent to socially might be more willing to listen. It’s still exhausting just to exist.

Yeah, I feel you. I don’t want to take up too much more of your time and energy. Any last words? Are you working on any upcoming projects?

A: I’m currently working on writing a zine about operating systems. Some other zines I have in the pipeline are: a zine about machine learning, a zine about compilers, a zine with interviews with some of my favorite coders — people who are using coding for social issues, art or music, and a zine about witchy trigonometry.

Amy doing a workshop at Write/Speak/Code in 2018. Image description: Amy is pictured in the center behind a laptop, mid sentence, holding one of her/their zines and a microphone.

Ooh, “witchy trigonometry?”

A: [Laughs]. It’s a zine that explains how to calculate the phases of the moon using trigonometry.

Wow. That’s amazing. What are you looking forward to for the New York Tech Zine Fair?

A: I’m really excited about the New York Tech Zine Fair because I’ve never been to a zine fair that was specifically focused on tech zines. I love SFPC and all of the work I’ve seen come out of it. I feel like it’s such a perfect host for a tech zine fair because they have everything I love about tech and zines — like the creativity, the inclusivity. I’m really excited to walk around and see what other people have made and buy lots of zines.

Computing & Stories Summit co-organized by Linda Liukas and Taeyoon Choi, featuring presenters Amy Wibowo, Jie Qi, Jenna Register, and Natalie Freed, assistant organizer Natalia Cabrera.

Would you consider zine making itself a technology?

A: At SFPC last year, I participated in Computing and Stories conference. Most people talked about how they used books and stories as a way to talk about technical concepts. Natalie Freed talked about how the art of bookbinding was a very technical thing and how there were different techniques around bookbinding — she had written a theorem of bookbinding and proved it to us with topology. I hadn’t ever thought of it in the converse, but yes, bookmaking is super technical. While that isn’t they way I’ve approached it, I love hearing from other people who have.

You’ll be doing a workshop, right? What is it going to be about?

A: Yeah, I will be. It’s going to be a zine writing workshop. It’s about zines as a way to make complex topics more accessible and understandable.

Amy’s workshop titled “Zines as a Friendly Introduction to Complex Topics” will be on Dec. 1 from 1 to 2 p.m. at the New York Tech Zine Fair.