An illustration of Wren McDonald drawing by Wren McDonald. Image description: A cartoon of a boyishly looking person hunched over a drafter’s desk with a backpack on. The person is drawing a smiley face sticking its tongue out. There is also a mechanical cord attached to the back of the person’s head.

I interviewed illustrator and cartoonist Wren McDonald. Not only has Wren’s work been featured in publications such as the New York Times, Wired and Boom! Studios, but Wren is also preceded by a long line of artists engaged in the cyberpunk genre, from Paul Verhoeven to Katsuhiro Otomo. Wren will be a vendor at the first ever New York Tech Zine Fair on Dec. 1 from 12-7 p.m. at the School for Poetic Computation.

Tell me a little bit about yourself—what’s going on in your world?

Wren: My name is Wren McDonald. I’m a cartoonist and illustrator. I make comics, mostly science fiction comics leaning towards cyberpunk. I have a graphic novel called SP4RX published by Nobrow which came out about a year and a half ago. I also self publish a lot of my own mini comics and zines that revolve around the same subject matter. I also do a lot of editorial illustrations for magazines and newspapers such as the New York Times and New Yorker.

You mentioned a lot of your work has a cyberpunk, and I kind of get this tech-dystopian, hacker feel to it. Do you identify as a hacker or programmer?

W: I don’t, actually, but it’s something that I’ve always been attracted to. I think that has a lot to do with growing up in the ‘90s and the things I was exposed to. Because for cyberpunk, the hayday in popular culture was definitely the ‘90s coming out from the real actual content in the ‘80s, and it becoming mainstream in the ‘90s. Being exposed to movies like Terminator 2 or Total Recall or the Matrix or Hackers. I think that had a big impact on me. Also around that time was the anime and manga boom of the ‘90s. A lot of that stuff was also really science fiction or cyberpunk heavy. One title that a huge affect on me was Akira by Katsuhiro Otomo. Also Ghost in the Shell by Mamoru Oshii. Blame! by Tsutomu Nihei. Evangeli—you know [laughs]. Just growing up in that. Not only that, but when I was a kid, not everyone had internet or computers in their homes. Now everyone has it in their pocket. Being there when the internet became a common tool that everyone used I think is really interesting.

How do you feel about being categorized within the cyberpunk, hacker aesthetic? Have you thought about breaking outside of that?

W: I feel like categorizing my work as cyberpunk gives people an entry point into what I do—like if you like cyberpunk, you might be interested in this. I don’t feel constrained to only do cyberpunk genre work. I’ve always been really interested in science fiction in general and some of my other work breaks into that. But I’ve also done a lot of other stuff, especially all of my editorial work, a lot of the jobs I work on have nothing to do with technology in anyway. So, yeah, I don’t think it’s crucial to me that I’m identified as like a ‘cyberpunk artist’ or something, but I think it can help in terms of introducing people to my work.

How does your personal relationship with technology inform the comics you’re creating?

W: I think that’s something that’s really interesting about cyberpunk as a genre in that, we kind of live in a cyberpunk or techno-dystopian world now. The aesthetics aren’t there yet, but day to day, government agencies and corporations are collecting your data, listening in, using it and putting a lot of energy and money into manipulating you. That’s the story we’ve been hearing for so long. And so I think the genre is still so relevant. I think it’s fun to use the tropes that are really campy now to talk about something that’s still so real and happening everyday.

How do you approach embedding politics or criticality into your work?

W: I don’t try to overthink it too much. I just respond to what’s happening around me. When I was working on my graphic novel SP4RX, I would watch the news every morning before I sat down to start working on it and a lot of times whatever was in the news that morning worked its way into the pages I was working on that day. I don’t think that I ever sit down with a really clear agenda. Everything I’m exposed to on a day to day basis works its way in. I think it’s really important, obviously, to pay attention to what’s going on around you. That makes the work relevant.

You make a distinction between comics and illustration in your work. How do you approach a comic versus an illustration project? Do you also think of your zines separately as well?

W: I definitely do. I feel like the comics and zines are much more personally driven work, so I feel like that’s much more “me” or maybe a purer sense of my point of view. Because a lot of times with illustration, I’m being commissioned to make an illustration for a magazine, newspaper or website that’s about someone else’s ideas. Sometimes I do like the personal illustration just for myself, but I feel like much more often I’m able to put personal energy into the comics and zines.

What sort of things do you think about when you sit down and make a zine?

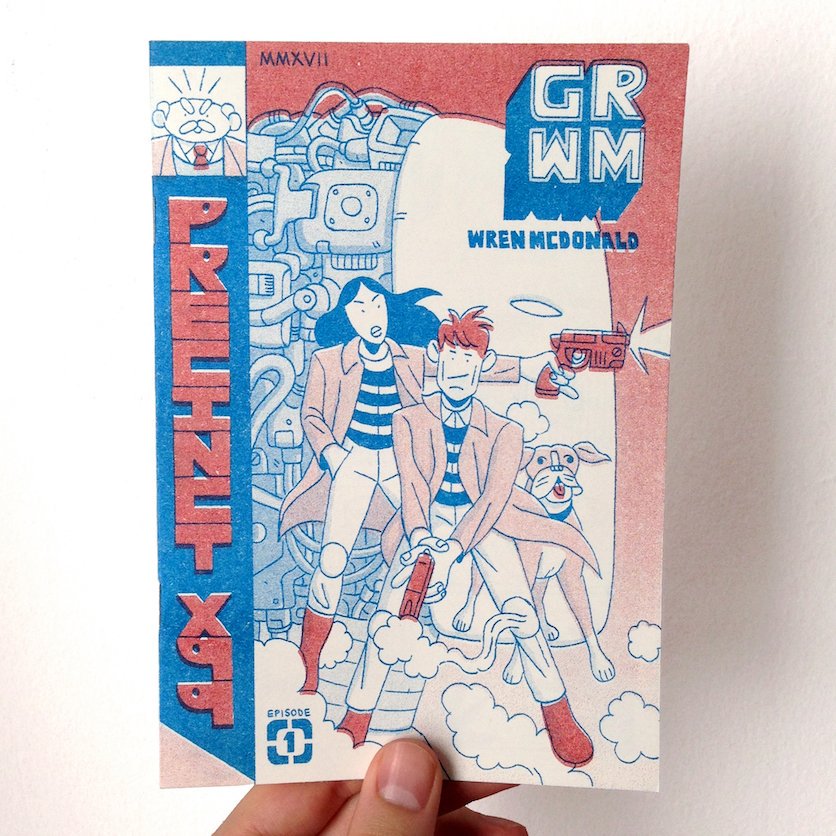

W: When I’m working on a comic or zine, I’m always thinking about the finished product. Even when I start drawing the first page, I really like to think ‘what is this going to feel like in the reader’s hands?’ I put a lot of thought into sizing and color and how it’s going to feel when they flip from page to page. Something I use for all my zines is a risograph copy machine. That’s something I was introduced to maybe, five years ago. It’s a really cool copy machine that allows you to print one color at a time, so the final effect is similar to screenprinting. It’s really fast and effective if you’re planning on making zines or askance, throwaway flyers—stuff like that.

Wren at the School of Visual Arts RisoLAB. Image courtesy Wren McDonald. Image description: Wren posing down on one knee with a peace sign next to a risograph machine. A black ink cartridge is extended out toward the center foreground of the image.

Wren at the School of Visual Arts RisoLAB. Image courtesy Wren McDonald. Image description: Wren posing down on one knee with a peace sign next to a risograph machine. A black ink cartridge is extended out toward the center foreground of the image.

Actually, right now, I’m the artist in residence at the School of Visual Arts RisoLAB, which has been great because their facilities are really nice. With the risograph, they’re always really finicky and I’ve owned my own and it’s always kind of a headache when you’re working on a zine like ‘is the machine gonna break down? I hope it doesn’t like, explode [laughs]. I hope I don’t run out of this supply or that supply.’ Those factors aren’t something I have to worry about at RisoLAB.”

Have you experienced any happy accidents from the risograph that you’ve tried to duplicate in your work?

W: Definitely. One thing that I think is really cool about risographs is that it adds an element of surprise to the final product. The registration, meaning the alignment of the colors, is not always exact. The texture can be a little bit off, sometimes there will be a small hole or scratch in the screen and you’ll get this textural effect which I think is really interesting. With my work, I’m using a lot of tropes from the ‘80s and ‘90s. The texture of the risograph has plays into that as well.

How would you describe your relationship with the people who read your comics and zines?

W: The way I interact with everyone who reads my work is primarily online. It’s funny because the whole world kind of exists there. When I do a show, it’s really interesting and really cool, to be honest, to see the people who I’ve interacted with online in real life. It just adds a physicality to it, like this is real. I think it’s cool to exist in a physical space and be able to talk zines and comics and everything.

How do you think technology factors into the context of zinemaking and the zine community today?

W: Zines hold a different space than they used to when they were first a thing. With the punk movement and everything, it was out of a necessity to get ideas out there and there was no other way to do that. Magazines or book publishers wouldn’t publish their ideas so, people were like ‘okay, I’m just going to go to the Xerox store, make these really cheaply and get the idea out there.’ Now with the internet and social media and everything, it’s so much easier to get your ideas out there, especially with something like Twitter. I think zines are now becoming more of an art object. I see zines becoming more and more expensive. I feel like it’s no longer a necessity. I don’t know, there’s a little bit of overlap there where it’s still about getting your idea out there and it’s especially really significant to be able to hand your idea to someone physically. At least in the comics zine community that I’m a part of, people are going there to get something from an artist that they like and primarily people already know what they’re getting themselves into.

In the current political moment where the corruption of the American government is at the forefront of public consciousness, how can we be critical with our work when this administration is shameless?

W: If we can do anything we can to point out the ridiculousness that’s going on, then hopefully we can contribute in some way to changing the public opinion that this is normal. Yeah, I don’t know if my cyberpunk zine is going to change the world—obviously not, but hopefully it can contribute a drop in the bucket to the few people that actually read it.

Precinct X99 Episode 1 by Wren McDonald. Image description: Wren McDonald holding the cover of Precinct X99 which shows a femme character in the background firing a pistol to the right, a masculine character in the foreground lowering a recently fired pistol and a dog sticking its tongue out between the two of them. The comic is colored in blue and red with a faded textural effect most likely achieved by a risograph printer.

What sort of things are grounding you right now? What are you inspired by?

W: To be honest, I love the same thing I’ve always been interested in which is science fiction from the ‘80s and ‘90s. Comics wise, I’m really into a series called Eden: It’s an Endless World! by Hiroki Endo. I just started re-watching Neon Genesis Evangelion, which is a favorite of mine. I don’t only expose myself to the older stuff. I still like going and seeing what’s new out there, especially when it comes to indie comics. I just did Comic Arts Brooklyn earlier this month and it’s so cool to walk around and see what everyone is doing and printing there and seeing how people are really pushing zinemaking.

What are you looking forward to in terms of the New York Tech Zine Fair?

W: I’m actually really excited about this fair because I feel like all the shows that I usually do are illustration and comic space. It’ll be really cool to have my work, which is primarily about technology in a space that is focused on that and be able to have people interact with my work and interact with others’ work who are also interested in science and technology. I think it’ll really be cool to have that new exposure.

Are you working on any new upcoming projects?

W: I’m currently working on a big—well, a medium sized mecha comic, so giant fighting robots. I won’t have that at the fair, but I will be doing reprints of my series Precinct X99 volumes one and two which have be out of print for a while.